CROM Continuous Reduced Order Models

Discretization-free Approximation of PDEs Using Implicit Neural Representations

In this blog post, I want to talk about continuous reduced order modeling (CROM) [ChenEtAl23], an innovative discretization-free reduced order modeling approach to approximate PDEs. The key novelty lies in utilizing an implicit neural representation (INR) to create a continuous representation of the reduced manifold, in contrast to the discrete representation commonly found in classical methods relying on reduction methods like proper orthogonal decomposition. Assuming prior knowledge of the PDE’s form, CROM involves using a solver to generate data for the training of a neural network (NN). This NN allows the generation of continuous spatial representations at any given time.

In order to evolve the dynamics at each time step, the original PDE is solved for the subsequent time point

The latent variable at time

Sounds complicated? Let’s go through it step by step but first things first.

Problem Setup

Many dynamical processes in engineering and sciences can be described by (nonlinear) partial differential equations (PDEs)

A common approach to solve PDEs for

To alleviate this bottleneck, reduced order models (ROMs) are used to significantly accelerate the calculations. The goal of reduced order modeling is to find efficient surrogate models that retain the expressiveness of the original high-fidelity simulation model while being much more cost-effective to evaluate. There are two main challenges:

- find expressive and low-dimensional coordinates to describe the vector field

- evolve the dynamics

While conventional approaches create a reduced order model for a fixed discretization of the PDE, the recently proposed CROM directly approximates the continuous vector field itself.

Conventional Reduced Order Models

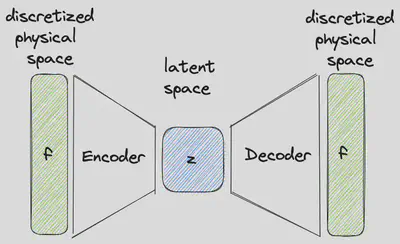

Popular methods to find a low-dimensional embedding on which a given system can be described on include linear methods like the principal component analysis (PCA) (also known as proper orthogonal decomposition (POD)) or its nonlinear counterpart autoencoders (AE). Those methods can be used to find a low-dimensional representation of the discretized vector field

but also to reconstruct the given discretization from this latent vector

In case of an autoencoder, these mappings are found by optimizing the reconstruction loss

for the networks’ weights

Just as there are different approaches for the reduction, there are also different methods to approximate the temporal dynamics of a system.

In case the underlying PDE is known, quasi-Newton solvers for implicit time integration of the latent dynamics on a continuously-differentiable nonlinear manifold have been used in [LeeCarlberg20].

When there is no knowledge about the underling equations present, some of the purely data-driven approaches try to directly approximate the time-dependent latent variable

What all those approaches share is that they rely on an already discretized vector field. Consequently, a change of resolution requires a new architecture and new training of the reduced order model. Furthermore, they don’t allow adaptive spatial resolution what can be useful in scenarios of varying intensity (low resolution when nothing is happening, high resolution when things get exciting) or for applications under changes of available computational resources. CROM claims to be able to overcome these disadvantages. So, let’s have a look how CROM differs from the previously presented approaches.

CROM

Embedding

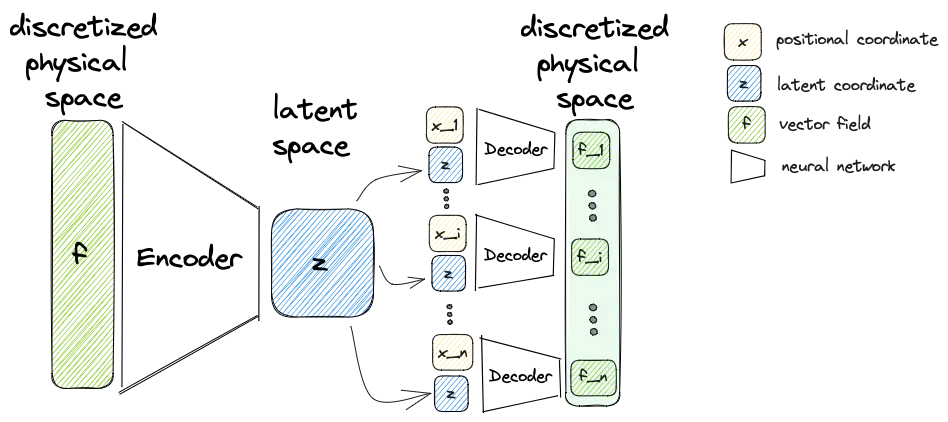

Similar to a conventional autoencoder approaches it constructs an encoder and a decoder. While there are no changes to the encoder compared to conventional methods, the decoder this time does not try to reconstruct a discretized vector field from the latent variable. Instead the decoder

takes the latent variable

To reproduce the behavior of a classical autoencoder, the decoder must be evaluated at all points of the discretization with different positional input.

However, it is also possible to reconstruct the vector field for any other point

Dynamics

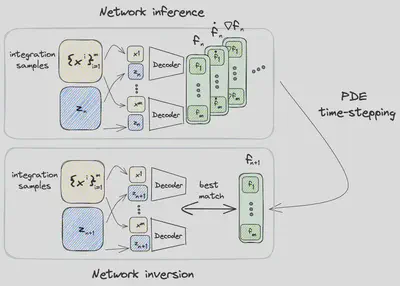

In contrast to conventional approaches CROM, evaluates the actual PDE for a small number of domain points

- network inference

- PDE time-stepping

- network inversion

Network Inference

During the first step of the computation of the latent space dynamics, all spatiotemporal information for the PDE time-stepping is gathered for the selected samples

PDE Time-stepping

Having all necessary information available, the PDE

Network Inversion

In the last step the dynamics on the reduced manifold are updated in such a way that

Examples

High-fidelity Model

The high-fidelity spatial vector field is discretized with

For a given initial condition and values of alpha and it can be solved using the following code snippet

import numpy as np

def solve_diffusion(Nt, Nx, dx, dt, alpha, u_init):

"""

Solve the diffusion equation u_t - alpha * u_xx = 0 with a first-order Euler scheme

:param Nt: number of time steps

:param Nx: number of spatial grid points

:param dx: spatial step size

:param dt: time step size

:param alpha: diffusion coefficient

:param u_init: initial condition

:return: u

"""

# create temperature vector of size (timesteps x spatial points)

u = np.zeros((Nt, Nx))

# set initial condition

u[0] = u_init

# Main time-stepping loop

for t in range(1, Nt):

# Compute the second derivative using finite differences

u_xx = np.zeros(Nx)

u_xx[1:Nx-1] = (u[t - 1, 2:] - 2 * u[t - 1, 1:-1] + u[t - 1, :-2]) / (dx ** 2)

# Update the solution

u_t = alpha * u_xx

# update solution using a first-order Euler scheme

u[t] = u[t - 1] + dt * u_t

return u

Reduced-Order Model

The latent dimension of the reduced order model is set to

A very simple implementation of the autoencoder for this example in PyTorch could look like this:

import torch

from torch import nn

# create autoencoder

class CROMAutoencoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, r, n_x, n_d=1, n_layers=1, n_neurons=128):

"""

:param r: latent space dimension

:param n_x: number of spatial points

:param n_d: number of coordinates required to describe the position (1 for 1D, 2 for 2D, ...)

:param n_layers: number of hidden layers in the encoder and decoder

:param n_neurons: number of neurons in each hidden layer

"""

super(CROMAutoencoder, self).__init__()

self.r = r

self.n_x = n_x

self.n_d = n_d

self.n_layers = n_layers

self.n_neurons = n_neurons

# create layers for the encoder

self.encoder_0 = nn.Linear(self.n_x, self.n_neurons)

self.encoder_0_act = nn.ELU(True)

# hidden layers

for i in range(n_layers):

setattr(self, f'encoder_{i + 1}', nn.Linear(self.n_neurons, self.n_neurons))

setattr(self, f'encoder_{i + 1}_act', nn.ELU(True))

setattr(self, f'encoder_{n_layers + 1}', nn.Linear(self.n_neurons, self.r))

# create layers for decoder

self.decoder_0 = nn.Linear(self.r + self.n_d, self.n_neurons)

self.decoder_0_act = nn.ELU(True)

# hidden layers

for i in range(n_layers):

setattr(self, f'decoder_{i + 1}', nn.Linear(self.n_neurons, self.n_neurons))

setattr(self, f'decoder_{i + 1}_act', nn.ELU(True))

# output layer with skip connection from spatial coordinate

setattr(self, f'decoder_{n_layers + 1}', nn.Linear(self.n_neurons + self.n_d, 1))

def encoder(self, u):

"""

Encoder that maps the vector field values to the latent space

:param u: (batchsize x n) vector field values

:return:

"""

for i in range(self.n_layers+2): # +2 for input and output layer

u = getattr(self, f'encoder_{i}')(u)

if hasattr(self, f'encoder_{i}_act'):

u = getattr(self, f'encoder_{i}_act')(u)

return u

def decoder(self, x, z):

"""

Decoder that maps the latent variable along with a spatial coordinate to the reconstructed vector field value

:param x: (batchsize x n) positional coordinates

:param z: (batchsize x r) latent variable

:return:

"""

# save batch size for reshaping later

batch_size_local = x.size(0)

# repeat z for every point in x (batch_size_local x n_x x r)

z = z.unsqueeze(1).repeat(1, x.size(1), 1)

# add new axis to x to the end (batch_size_local x n_x x n_d)

x = x.unsqueeze(2)

# concatenate x and z

decoder_input = torch.cat((x, z), dim=2)

# reshape for decoder so that all the points are processed at once (batchsize = batch_size_local * n_x)

decoder_input = decoder_input.view(-1, self.r + self.n_d)

u_ = decoder_input

for i in range(self.n_layers + 1): # +1 for input layer

u_ = getattr(self, f'decoder_{i}')(u_)

if hasattr(self, f'decoder_{i}_act'):

u_ = getattr(self, f'decoder_{i}_act')(u_)

# stack x and u_ (skip connection from x to output layer)

output_input = torch.cat((x.view(-1, self.n_d), u_), dim=1)

u_ = getattr(self, f'decoder_{self.n_layers + 1}')(output_input)

# reshape x_rec

u_rec = u_.view(batch_size_local, -1)

return u_rec

def forward(self, x, u):

"""

:param x: (batchsize x n) positional coordinates

:param u: (batchsize x n) vector field values

"""

# encode input to latent space

z = self.encoder(u)

# reshape x_rec

u_rec = self.decoder(x, z)

return u_rec

In contrast to the implementation of the original paper, I don’t use convolutional layers for simplicity and introduced a skip-connection in the decoder from the spatial coordinate

Hereafter, we can evolve the latent dynamics in time using only a few (in this case

def time_stepping(model, n_t, n_x, dt, x_support, support_point_indices, alpha_support, u_init):

"""

Time evolution of the latent variable by evaluating the original PDE on a small number of support points

and then finding the latent variables that matches best to the found evolved vector field values

:param model: CROMAutoencoder model

:param n_t: number of time steps

:param n_x: number of spatial grid points

:param dt: time step size

:param x_support: spatial grid points that are evaluated during time stepping

:param support_point_indices: indices of the support points

:param alpha_support: diffusion coefficients at the support points

:param u_init: initial condition of the vector field

:return:

"""

# encode initial condition

z_init = model.encoder(torch.from_numpy(u_init).float()).detach().requires_grad_()

# create latent vector of size (timesteps x (spatial points + 1))

z = torch.zeros((n_t, model.r))

# set initial condition

z[0] = z_init

# Main time-stepping loop

for i_time in range(1, n_t):

# compute the second order spatial gradient using autograd

hessian = torch.func.hessian(model.decoder, argnums=0)(x_support, z[i_time-1:i_time]).squeeze()

u_xx = torch.diagonal(torch.diagonal(hessian, dim1=0, dim2=1), dim1=0, dim2=1).detach().squeeze()

# apply boundary conditions

for i, index in enumerate(support_point_indices):

if index == 0 or index == n_x:

u_xx[i] = 0

# get time derivative

u_t = alpha_support * u_xx

# evolve latent variable in time (this part uses the linearized version instead of Gauss-Newton solver)

res = u_t

jac = torch.func.jacrev(model.decoder, argnums=1)(x_support, z[i_time-1:i_time]).detach().squeeze()

vhat = torch.inverse(torch.matmul(jac.transpose(1, 0), jac)).matmul(jac.transpose(1, 0)).matmul(res)

vhat = vhat.view(1, 1, -1) # (dim: ? x ? x r)

z[i_time] = z[i_time-1] + vhat * dt

return z

From this latent time series, we can reconstruct the full vector field at arbitrary points

Concluding Remarks

CROM is a very powerful discretization-free ROM scheme for PDEs. The authors showed that it can outperform conventional approaches regarding accuracy and resource demands while offering adaptive spatial resolutions. Nevertheless, it shares some limitations with classic data-driven ROM approaches like the dependency on the training data, i.e. it won’t generalize well to unseen scenarios. In contrast to complete data-driven approaches it offers a nice blend of ML and PDE solutions at the cost of increased method complexity.

Should you use CROM?

Well, it depends. It is a very promising method which is likely to pave the way for many more great research projects. Especially, when you can take advantage of adaptively adjusting your discretization ,it is worth a try. If you, however, don’t mind the discretization present in your problem, you can still go for the more conventional approaches and in that case even consider whether linear reduction (PCA) isn’t suitable for your certain problem.